In Praise of Plagiarism

[in-process draft, based on oral presentation. Please cite or quote from one of the published versions.]

Note: This work began with a presentation to an "Effective Teaching Institute" at St. Thomas, on 7 December 2001. It has been revised a number of times. Excerpts, adaptations, and spinoffs from it have been delivered at various conferences and published in various university teaching newsletters. Published versions are:The "information technology revolution" is almost always presented as having cataclysmic consequences for education -- sometimes for the better, but more often, of course, for the worse. In postsecondary circles, perhaps the most commonly apprehended cataclysm is "Internet Plagiarism." When a university subscribes to turnitin.com, the local media invariably pick up the story -- "Students to Learn that Internet Crime Doesn't Pay" -- with the kind of alacrity usually reserved for features on political sex scandals or patronage payoffs. [more] When the newest cheating scandal surfaces at some prestigious southern university known for its military school style "honor code," the headlines leap across the tabloids like stories on child molestation by alien invaders."Whose Silverware Is This? Promoting Plagiarism Through Pedagogy (Or, Peter Piper Picked a Peck of Purloined Passages)." Plagiarism: Prevention, Practice & Policy, 28-30 June 2004: Proceedings. Ed. Andy Peden Smith and Fiona Duggan. Newcastle-Upon-Tyne: Northumbria University Press, 2005. 265-274.

"Two Cheers for Plagiarism." Inkshed Newsletter 20:3 (Autumn 2003), 10-18.

"Four Reasons to be Happy about Internet Plagiarism." Teaching Perspectives (St. Thomas University) 5 (December 2002) [1-5]. Repr. Teaching Options Pedagogiques 6:4 (University of Ottawa) (August 2003), 3-5; repr. [as "Let's Hear it for Internet Plagiarism"] Teaching & Learning Bridges 2:3 (University of Saskatchewan) (November 2003), 2-5; Teaching Matters Newsletter (University of New Brunswick, Saint John) (January 2007) 6-9; in Critical Thinking and Logic Skills for Life, ed. Judith Boss (McGraw-Hill, in press).

It's almost never suggested that all this might be something other than a disaster for higher education. But that's exactly what I want to argue here. I believe the challenge of easier and more convenient plagiarism is to be welcomed.

I'd like to begin, though, by making a firm distinction -- one the media never makes, and academia almost never -- between "cheating" and "plagiarism." When we talk about these phenomena, the two terms tend to be conflated, and discussions of "plagiarism" often include, or merge into, lamentations about the the increasing frequency of clever forms of cheating -- pagers in the exam room, answers in the lining of ball caps or recorded in the cassettes or CDs playing in the Walkman.

This, however, is not plagiarism. In general, these are ways of extending the technology of memory. Is it a great deal different to memorize a few hundred lines than it is to write them in your hat, or burn them onto a CD? Memorizing wouldn't be called cheating, of course, but perhaps it should be. And it's important to bear in mind that what's memorized probably will last a shorter time than the CD -- or even the notes in the hat.

It's pretty difficult, after all, to plagiarize on an examination. Two conditions have to be met: you have to know in advance what the question will be and you have to have a source for a text that will answer the question, and record that on your CD or get it into your hat lining. This might happen, of course, and would technically be plagiarism. But, as the false Queen used to sneer in Jim Henson's Frog Prince, "It doesn't seem so likely, though, does it?"

It's important, then, to recognize not only that not all cheating is plagiarism. It's even more important to see that only an extremely small proportion of the plagiarism that actually occurs is cheating. The more common forms of plagiarism -- almost exclusively, in the production of term papers, research essays, etc. -- are mostly matters of ignorance rather than deliberate, "let's buy this term paper" dishonesty.

As everybody in academia knows, plagiarism involves taking an utterance which you didn't originally utter, and, without acknowledging that it's not your own original invention, allowing or inviting others to attribute it to you. The OED's first definition is "the wrongful appropriation or purloining, and publication as one's own, of the ideas, or the expression of the ideas (literary, artistic, musical, mechanical, etc.) of another."

In the world beyond the campus, as James Kincaid pointed out in a brilliant New Yorker piece about this phenomenon, it's pretty rare for this to happen -- or, more accurately, it's pretty rare for anyone to call it plagiarism. In most cases, as Kincaid says, it's a perfectly normal way of proceeding. Newspaper writers and editors "boilerplate in" paragraphs lifted from the AP or Reuters wire and produce stories which are pastiches of other stories; repeat explanatory paragraphs for the sixth time (how many ways, after all, are there to remind the reader what happened on September 11, 2001, or December 7, 1941, and why would we ask a reporter to come up with a new one?) and so forth. And in cases where writing isn't published (as, after all, most isn't), one might guess that 80% of what gets put down in businesses and bureaucracies is copied in from elsewhere.

Further, and more important, the bizarre modern (and, it's arguable, Western) emphasis on "originality" in utterances runs counter to most language practice. It's not only Bakhtin who's pointed out that most of what we say is put together from scraps and rags of other people's utterances (Bakhtin, however, has been most persuasive in arguing that pretty much anything we can say about orality can also be said about literacy.) This is perhaps the most radical part of the argument against the hysteria over plagiarism, and the one most likely to attract fulminations of the kind Kincaid's article generated from, for example, Seth Rogovoy, writing on "the Berkshire Web," who says,

"Most of us will cede that absolutely pure 'originality' is an over-the-rainbow idea; none of us invent the language we employ, our education, our culture, or our history," writes Kincaid. I put that sentence in quotes to denote that the words are his, not mine. The idea those words express is indeed provocative, perhaps even one worth thinking about. But just because we do not "invent" our own languages from the ground up doesn't mean we cannot tell the difference between plagiarism -- the act of stealing and using the ideas or writings of another as one's own, to paraphrase the American Heritage Dictionary's definition -- and the influence of our education when it comes to original expression.The ease with which extraordinarily complicated issues are skated over there is breathtaking. It's easy to say that "everybody knows" what plagiarism is; unfortunately, there's lots of evidence to suggest some pretty deep-seated confusion, among scholars, faculty, administrations, and students, about what's happening when people engage in the interchange and exchange of ideas that is the lifeblood of academia.

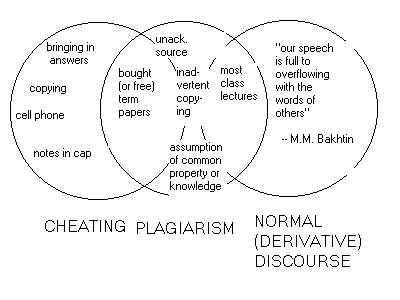

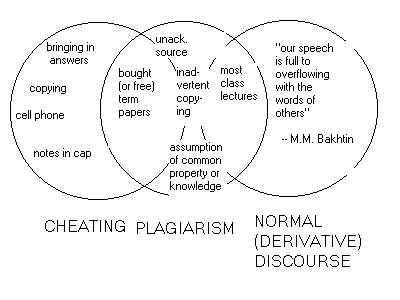

Here's a diagram which I offer as a way of thinking about the situation of discourse and the distinctions among "cheating," "plagiarism," and ordinary discourse.

I've offered there some illustrative examples of each -- except what I've called "normal discourse," since I assume in that case everyone can supply her own. The crucial point here is that the categories overlap: there are times when plagiarism is clearly cheating on the same order as copying answers on a test. The typical occurrence is the purchased term paper -- or, in the "good old days," the one retrieved from the frat house files. Similarly, there are times when plagiarism and normal discourse overlap -- the usual classroom lecture or textbook chapter, for instance, is full of ideas and phrases which owe their origins to others -- and which, were they in a student paper, we'd probably insist be "acknowledged" or "documented" or "cited" -- but which, here, we take it for granted are more like the usual discourse all of us engage in and so don't need to follow some abstract rule of attribution.

Typically -- indeed, almost universally -- the plagiarism which is the subject of ominous and threatening pronouncements in university calendars happens when the student turns in an "essay," a "research paper," a "term paper" -- and we find in it those telltale rhetorical moves that signal, "this writing was not produced by an undergraduate doing an assignment." And we tend to react like this:

Stopped by Plagiarism, on a Snowy EveningThat was posted to an email list concerned with the study of the eighteenth century, after a Thanksgiving weekend which the list member had spent marking papers. Her husband wrote it while watching her suffer through the "English teacher's burden" of endlessly grading piles of paper. It's clever, even brilliant, as a parody of the Frost poem, and it made me laugh out loud when it was posted. But it's also an example of a mindset which we bring to student work ("the little jerk") -- and one which I argue is deeply and profoundly threatened by the tidal wave of internet plagiarism . . . and ought to be.Whose words these are I think I know

(They're surely not this student's, though)

Apparently his time's too dear,

And composition far too slow.The little jerk may think it queer

That I would have a problem here

And ask for work that's sure to break

His comfortable routine this year.Another painful call to make

To ask if there is some mistake.

Will he deny, or maybe weep,

And threaten then his life to take?This unclean harvest I must reap

For I have deadlines I must keep;

And piles to grade before I sleep,

And piles to grade before I sleep.-- Dallas Sommers (Posted on "C18-L" by Susan Sommers, St. Vincent College, 26 November 2001) [http://f05n16.cac.psu.edu/cgi-bin/wa?A2=ind0111&L=c18-l&O=A&P=25024 ]

I believe the challenge of easier and more convenient plagiarism is to be welcomed. This rising tide threatens to change things -- for, I predict and hope, the better. Here are some specific practices which are threatened by the increasing ease with which plagiarism can be committed.

1. The institutional rhetorical writing environment (the "research paper," the "literary essay," the "term paper") is challenged by this, and that's a good thing. Our reliance on these forms as ways of assessing student skills and knowledge has been increasingly questioned by people who are concerned with how learning and assessment take place, and can be fostered, and particularly with how the ability to manipulate written language ("literacy") is developed. The assumption that a student's learning is accurately and readily tested by her ability to produce, in a completely arhetorical situation, an artificial form that she'll never have to write again once she's survived formal education (the essay examination, the formal research paper), is questionable on the face of it, and is increasingly untenable. If the apprehension that it's almost impossible to escape the mass-produced and purchased term paper leads teachers to create more imaginative, and rhetorically sound, writing situations in their classes, the advent of the easily-purchased paper from schoolsucks.com is a salutary challenge to practices which ought to be challenged.

One good, clear example of the argument which can be mounted against generic term paper assignments and in favor of assignments which track that writing process and / or are specific to a particular situation is in Tom Rocklin's online "Downloadable Term Papers:What's a Prof. to Do?" ( http://www.uiowa.edu/%7Ecenteach/resources/ideas/term-paper-download.html ). Many other equivalent arguments that assignment can be refigured to make plagiarism more difficult -- and offer more authentic rhetorical contexts for student writing -- have been offered in recent years.

A posting to the "College-Talk" NCTE list, responding to a description of an empty writing exercise imposed on elementary school students, responded, in part: "This sheds a lot of light on things and helps me, just as seeing the writing projects my 11-year-old daughter is assigned, to understand how our institution of education works all of the creativity, meaning, and enjoyment out of writing so that by the time our students are 18 and facing us in our classrooms, they are absolutely certain that 1) they are not "real" writers 2) they cannot write and will never be able to write 3) they hate writing, don't want to do it, and find no purpose in it other than torture."

I'm unconvinced that we can address this problem by assuring students that "they are real writers with meaningful and important things to say," or invite them to revise their work where we can see the revisions, as long as we continue giving them more decontextualized, audienceless and purposeless writing exercises. Having something to say is -- for anybody except, maybe, a Romantic poet -- absolutely indistinguishable from having someone to say it to, and an authentic reason for saying it. To address this problem, I believe, we need to rethink the position of writing in student's lives and in the curriculum. One strong pressure to do that is the increasing likelihood that empty exercises can by fulfilled by perfunctory efforts, or borrowed texts.

2. The institutional structures around grades and certification are challenged by this, and that's a good thing. Perhaps more important is the way plagiarism challenges the overwhelming pressure for grades which our institutions have created and foster, and which has as its consequence the pressure on many good students to cut a corner here and there (there's lots of evidence that it's not just the marginal students in danger of failing who cheat; it's as often those excellent students who believe, possibly with some reason, that their lives depend on keeping their GPA up to some arbitrary scratch). An even more central consideration is the way the existence of plagiarism itself challenges the way the university structures its system of incentives and rewards, as a zero-sum game, with a limited number of winners.

University itself, as our profession has structured it, is the most effective possible situation for encouraging plagiarism and cheating. If I wanted to learn how to play the guitar, or improve my golf swing, or write HTML, "cheating" would be the last thing that would ever occur to me. It would be utterly irrelevant to the situation. On the other hand, if I wanted a certificate saying that I could pick a jig, play a round in under 80, or produce a slick Web page (and never expected actually to perform the activity in question), I might well consider cheating (and consider it primarily a moral problem). This is the situation we've built for our students: a system in which the only incentives or motives anyone cares about are marks, credits, and certificates. We're not entirely responsible for that -- government policies which have tilted financial responsibility for education increasingly toward the students and their families have helped a lot -- but the crucial factor has been our insistence, as a profession, that the only motivation we could ever count on is what is built into the certification process. When students say -- as they regularly do -- "why should I do this if it's not marked?" or "why should I do this well if it's not graded?" or even "I understand that I should do this, but you're not marking it, and my other professors are marking what I do for them," they're saying exactly what educational institutions have been highly successful at teaching them to say.

They're learning exactly the same thing, with a different spin, when we tell them that plagiarism is a moral issue. We're saying that the only reason you might choose not to do it is a moral one. But think about it: if you wanted to build a deck and were taking a class to learn how to do it, your decision not to cheat would not be based on moral considerations.

3. The model of knowledge held by almost all students, and by many faculty -- the tacit assumption that knowledge is stored information and that skills are isolated, asocial faculties -- is challenged by this, and that's a good thing. When we judge essays by what they contain and how logically it's organized (and how grammatically it's presented) we miss the most important fact about written texts, which is that they are rhetorical moves in scholarly and social enterprises. In recent years there have been periodic a assaults on what Paolo Freire (1974) called "the banking model" of education (and what, more recently, Tom Marino [2002], writing on the POD list, referred to as "educational bulimics"). Partisans of active learning, of problem- and project-based learning, of cooperative learning, and of many other "radical" educational initiatives, all contend that information and ideas are not inert masses to be shifted and copied in much the way two computers exchange packages of information, but rather need to be continuously reformatted, reconstituted, restructured, and exchanged in new forms, not only as learning processes but as the social basis of the intellectual enterprise. A model of the educational enterprise which presumes that knowledge comes in packages (one reinforced by marking systems which say you can get "73%" of Renaissance literature or introductory organic chemistry) invites learners to import pre-packaged nuggets of information into their texts and their minds.

Similarly, a model which assumes that a skill like "writing the academic essay" is an ability which can be demonstrated on demand, quite apart from any authentic rhetorical situation, actual question, or expectation of effect, virtually prohibits students from recognizing that all writing is shaped by rhetorical context and situation, and thus renders them tone-deaf to the shifts in register and diction which make so much plagiarized undergraduate text instantly recognizable. (The best documentation of the strangely arhetorical situation in which student writing lives is in the work done as part of the extensive study of school-based and workplace writing at McGill and Carleton Universities, reported in Worlds Apart and Transitions).

4. But there's a reason to welcome this challenge that's far more important than any of these -- more important, even, than the way the revolutionary volatility of text mediated by photocopying and electronic files have assaulted traditional assumptions of intellectual property and copyright by distributing the power to copy beyond those who have the right to copy. It's this: by facing this challenge we will be forced to help our students learn what I believe to be the most important thing they can learn at university: just how the intellectual enterprise of scholarship and research really works. Traditionally, when we explain to students why plagiarism is bad and what their motives should be for properly citing and crediting their sources, we present them in terms of a model of how texts work in the process of sharing ideas and information which is profoundly different from how they actually work outside of classroom-based writing, and profoundly destructive to their understanding of the assumptions and methods of scholarship.

When you look at the usual set of examples of plagiarism as it occurs in student papers, for example, what you see are almost invariably drawn from kinds of writing obviously and radically identifiable as classroom texts. And how classroom texts relate to or use the ideas and texts of others is typically very different from how they're used in science, scholarship, or other publications. There are many such explanatory examples in print and on the Web; let me take one from the Northwestern University "The Writing Place" Web site. They offer the following as an example of an acceptable and properly credited paraphrase:

OriginalWhat is clearest about this is that the writer of the second paragraph has no motive for rephrasing the passage other than to put it into different words. Had she really needed the entire passage as part of an argument or explanation she was offering, she would have been far better advised to quote it directly. The paraphrase neither clarifies nor renders newly pointed; it's merely designed, it seems, to demonstrate to a skeptical reader that the writer actually understands the phrases she is using in her text. Without more context than the Northwestern site gives us, it's difficult to know exactly how the paragraph functions in a larger rhetorical purpose (if it does).But Frida's outlook was vastly different from that of the Surrealists. Her art was not the product of a disillusioned European culture searching for an escape from the limits of logic by plumbing the subconscious. Instead, her fantasy was a product of her temperament, life, and place; it was a way of coming to terms with reality, not of passing beyond reality into another realm.

Hayden Herrera, Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo (258)

Paraphrase

As Herrera explains, Frida's surrealistic vision was unlike that of the European Surrealists. While their art grew out of their disenchantment with society and their desire to explore the subconscious mind as a refuge from rational thinking, Frida's vision was an outgrowth of her own personality and life experiences in Mexico. She used her surrealistic images to understand better her actual life, not to create a dreamworld (258).

Key words and phrases in the original are in boldface. The changes in wording and sentence structure in the paraphrase are underlined.

But published literature is full of examples of writers using the texts, words and ideas of others to serve their own immediate purposes. Here's an example of the way two researchers opened their discussion of the context of their work in 1984:

To say that listeners attempt to construct points is not, however, to make clear just what sort of thing a 'point' actually is. Despite recent interest in the pragmatics of oral stories (Polanyi 1979, 1982; Robinson 1981), conversations (Schank et al. 1982), and narrative discourse generally (Prince 1983), definitions of point are hard to come by. Those that do exist are usually couched in negative terms: apparently it is easier to indicate what a point is not than to be clear about what it is. Perhaps the most memorable (negative) definition of point was that of Labov (1972: 366), who observed that a narrative without one is met with the "withering" rejoinder, "So what?" (Vipond & Hunt, 1984)It is clear here that the motives of the writers do not include prevention of charges of plagiarism; moreover, it's equally clear that they are not -- as they would be enjoined to do by the Northwestern Web site -- attempting to "Cite every piece of information that is not a) the result of your own research, or b) common knowledge." What they are doing is more complex. The bouquet of citations offered in this paragraph is informing the reader that the writers know, and are comfortable with, the literature their article is addressing; they are moving to place their argument in an already existing written conversation about the pragmatics of stories; they are advertising to the readers of their article, likely to be interested in psychology or literature, that there is an area of inquiry -- the sociology of discourse -- that is relevant to studies in the psychology of literature; and they are establishing a tone of comfortably authority in that conversation by the acknowledgement of Labov's contribution and by using his language --"withering" is picked out of Labov's article because it is often cited as conveying the power of pointlessness to humiliate (I believe I speak with some authority for the authors' motives, since I was one of them).

Scholars -- writers generally -- use citations for many things: they establish their own bona fides and currency, they advertise their alliances, they bring work to the attention of their reader, they assert ties of collegiality, they exemplify contending positions or define nuances of difference among competing theories or ideas. They do not use them to defend themselves against potential allegations of plagiarism.

The clearest difference between the way undergraduate students, writing

essays, cite and quote and the way scholars do it in public is this: typically,

the scholars are achieving something positive; the students are avoiding

something negative. A chart identifying the reader's primary concerns in

dealing with class texts and workplace texts, offered by Freedman &

Adam (2000:134) is clear:

| Case-study [class] writing | Workplace writing |

Writer’s knowing; therefore

|

Ultimate senior reader; therefore

|

It seems clear that the conclusion we're driven to is this: offering lessons and courses and workshops on "avoiding plagiarism" -- indeed, posing plagiarism as a problem at all -- begins at the wrong end of the stick. It might usefully be analogized to looking for a good way to teach the infield fly rule to people who have no clear idea what baseball is.

"Cheating" is an issue one might want to address explicitly, though even there, if pushed, I might argue that to invoke the concept of "cheating" is, by implication, to agree that this is a game, with rules, a score, and winners and losers. That's part of the model of marks, GPAs and certification which, I think, is part of the problem, part of the reason most of the members of an engineering class might, when assigned a programming problem, simply boilerplate the code into their answer. If a gradable product is the only goal, who would run the risk of writing bad code? The right answer's already out there. No professional engineer would waste the time to re-invent a routine if a perfectly serviceable one already existed.

But, whatever we do, let's begin by keeping plagiarism and cheating separate.

Davidson, Michelle. "Re: [college-talk] Fwd: jan's 3rd-grade rant! IMPASSIONED

and long! boo hiss!..." College-Talk <college-talk@serv1.ncte.org>,

14 February 2002.

[ http://www.ncte.org/lists/college-talk/archives/feb2002/msg00055.html

]

Dias, Patrick. "Writing Classrooms as Activity Systems." Transitions: Writing in Academic and Workplace Settings, ed. Patrick Dias and Anthony Paré. Cresskill, New Jersey: Hampton Press, 2000. 11-29.

Dias, Patrick, Aviva Freedman, Peter Medway, and Anthony Paré, eds. Worlds Apart: Acting and Writing in Academic and Workplace Contexts [The Rhetoric, Society and Knowledge Series]. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. 1999

Freedman, Aviva, and Christine Adam. “Bridging the Gap: University-Based Writing that is More than Simulation.” Transitions: Writing in Academic and Workplace Settings, ed. Patrick Dias and Anthony Paré. Cresskill, New Jersey: Hampton Press, 2000. 129-144.

Freire, Paolo. The Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Seabury, 1974. (Translated from the original Portuguese (1968) by Myra Bergman Ramos).

Kincaid, James R. "Purloined letters." The New Yorker 72:43 (20 January 1997): 93 ff. [Available on line, on Ted Nellen's "Cyber English" Web site, at http://www.tnellen.com/cybereng/ethics/purloined.html ]

Marino, Tom. "Re: How many minutes per class day does the typical student

study?" Professional & Organizational Development Network in Higher

Education <POD@listserv.nd.edu>, 28 May 2002.

[ http://listserv.nd.edu/cgi-bin/wa?A2=ind0205&L=pod&O=D&P=14486

].

Rogovoy, Seth. "Plagiarism, politics and England's setting sun."

The

Berkshire Web, Williamstown, Mass., Jan. 25, 1997.

[ http://www.berkshireweb.com/rogovoy/other/england.html

]

Sommers, Susan. "It's that time of year again..." 18th Century Interdisciplinary Discussion <C18-L@LISTS.PSU.EDU>, 26 November 2001. [ http://f05n16.cac.psu.edu/cgi-bin/wa?A2=ind0111&L=c18-l&O=A&P=25024 ]

Vipond, Douglas, and Russell A. Hunt "Point-Driven Understanding: Pragmatic and Cognitive Dimensions of Literary Reading." Poetics 13 (June 1984), 261-277.

"Avoiding Plagiarism." The Writing Place, Northwestern University. [ http://www.writing.nwu.edu/tips/plag.html ]

This is the text of one of the most thoughtful and useful email messages I've ever received on a listserv. I've reformatted it and generally cleaned it up for the current purpose. Nick Carbone is the author of Writing Online: A Students' Guide to the Internet and World Wide Web.

I don't like any of the plagiarism software because it emphasizes detection after the fact instead of teaching. And none of it can distinguish between properly quoted/paraphrased sources and (it will flag a block quote as plagiarized) and cut and paste jobs.

So I recommend these sources instead. Especially the book mentioned at the end.

Part 1. Resources for Assignment Design and Understanding Plagiarism

You know the the things to do in an assignment: avoid giving hackneyed assignments, have students write multiple drafts, have students maintain annotated bibliographies, and so on. All very good ideas. More on these strategies is available, in more detail and with some slight variations, at the following Web sites:

"Plagiarism: a misplaced emphasis," by Brian Martin

( http://www.uow.edu.au/arts/sts/bmartin/pubs/94jie.html

).

This scholarly essay looks at the prevalence of ghostwriting, and nonattribution done by teachers and administrators that makes up much of the workaday world of academia (as distinct from the writing done in scholarly journals)."Preventing Academic Dishonesty," by Barbara Gross Davis

A broader view of plagiarism, with good teachng strategies and a good bibliography."Plagiarism in Colleges in the USA," by Ronald B. Standler

Standler, an attorney in Massachusetts, provides an overview of case law on plagiarism, and offers opinions on legal issues involving plagiarism accusations and procedures. ."Plagiarism and the Web," by Bruce Leland

A good nuts and bolts site; great for a quick reference or as a resource for planning a workshop for faculty.Bibliography of plagiarism articles by Rebecca Moore Howard

Howard is one the leading plagiarism scholars in composition; this page"The New Plagiarism: Seven Antidotes to Prevent Highway Robbery in an Electronic Age," by Jamie McKenzie

lists several of her most important articles.

"Downloadable Term Papers: What's a Prof. to Do?," by Tom Rocklin

( http://www.uiowa.edu/%7Ecenteach/resources/ideas/term-paper-download.html

)

Rocklin's message: better assignments, better assignments, better assignments.

"Anti-Plagiarism Strategies for Research Papers," by Robert Harris

( http://www.virtualsalt.com/antiplag.htm

)

This site offers good assignment strategies, a reminder to distinguish

between intentional cheating and poor source management and integration

(mistakes in paraphrasing and quoting).

I've been visiting Harris' pages for years, not only on plagiarism, but also for his advice on teaching research online. I've always found his advice sensible, balanced, and consistent. Harris is also the author of a new book on plagiarism, The Plagiarism Handbook: Strategies for Preventing, Detecting, and Dealing with Plagiarism (2001, from Pyrczak Publishing). Details on how to order it, the table of contents, and other information can be found at the Web site for the book, ( http://www.antiplagiarism.com/ ).

I really like Harris's book because he reminds teachers again and again to remember the student point of view. Here are some (not all) of his major points:

To help you talk about plagiarism with your students, his book offers a collection of cartoons that illustrate various points of views about plagiarism (two examples can be found on the Web site), which teachers are invited to use as handouts, for class discussion, or in teacher training workshops. Harris also includes several appendices with exercises to help with correct quoting, paraphrasing, and summarizing; sample plagiarism statements and policies; a list of useful search engines, including databases; a list of term paper mills (which can often be searched by teachers); and useful Web links and articles.

All in all, Harris offers in this book a good starting place for developing your own wise response to plagiarism, giving you the tools you need to be proactive rather than reactive. Unlike the message from Turnitin.com, the book emphasizes the role of good teaching and classroom planning, doesn't assume students are criminals, and offers a range of resources teachers can use to be better prepared.

As of May, 2002 the opening page for turnitin.com included the following promise: "includes Peer Review, the only online collaborative learning solution to protect against peer collusion."

-- Tom Lehrer, "Lobachevsky"

Siting Sources.

Subject(s): BARRIE, John; PLAGIARISM

Source: Wall Street Journal - Eastern Edition, 9/16/2002, Vol.

240 Issue 54, pR4, 0p Author(s): Reagan, Brad Abstract:

Interviews John Barrie, who offers services for catching student plagiarizers

via Turnitin.com, about the growth of his business.

plagiarism: Prevention, Not Prosecution.

Subject(s): PLAGIARISM -- United States; STUDENTS -- United States;

INTERNET (Computer network) -- United States Source: Book Report,

Sep/Oct2002, Vol. 21 Issue 2, p26, 2p, 1bw

Author(s): Janowski, Adam

Abstract: Focuses on the methods used by teachers to prevent

plagiarism in the U.S. Definition of plagiarism; Influence of the internet

on the rapid increase of plagiarism problems in schools; List of several

sources to assist students and teachers in their research.

Graded Multiple Choice Questions: Rewarding Understanding and Preventing Plagiarism. Subject(s): TRUE-false examinations; ACADEMIC achievement Source: Journal of Chemical Education, Aug2002, Vol. 79 Issue 8, p961, 4p, 1 chart Author(s): Denyer, Gareth; Hancock, Dale Abstract: Examines the adoption of multiple choice questions and true/false questions in student academic assessment. Effects of mechanized assessments on student learning; Usefulness of marking scheme in mathematics examinations; Application of scanning software in student answer sheets.

Professors Use Technology to Fight Plagiarism.

Subject(s): PLAGIARISM -- United States; COMPUTER software --

United States Source: Computer, Aug2002, Vol. 35 Issue 8, p24,

2p Author(s): Paulson, Linda Dailey Abstract: Reports

the use of plagiarism-detection software by teachers in the U.S. Increase

in the demand for the software; Development of the WordCheck antiplagiarism

programs; Support of academics in anti-plagiarism tools. INSET: Teaching

IT in the Inner City, by Linda Dailey Paulson.

WHY I..

Subject(s): PLAGIARISM; LITERATURE

Source: Times Higher Education Supplement, 7/26/2002 Issue 1548,

p14, 1/5p Author(s): Atkinson, Valerie Abstract:

Focuses on the topic of plagiarism on literature. Cardinal sin of the academe;

Violation of the scholarly standards; Comparison of plagiarism with adultery.

It's a Bird, It's a Plane, It's Plagiarism Buster!

Subject(s): PLAGIARISM; CHEATING (Education); COLLEGE students;

AUTHORSHIP Source: Newsweek, 7/15/2002, Vol. 140 Issue 3, p12,

1p, 1c Author(s): Silverman, Gillian

Abstract: Reflects on searching for cases of plagiarism in college

papers. Way in which students may cheat by stealing material from the Internet;

Web sites which provide students with papers to copy; Belief that the life

styles of students do not leave them enough time to do their schoolwork.

Apologies for multiple postings

************************************************

25th November 2002

10 15am - 4 00pm

65 Davies Street, London W1

led by Jude Carroll

150.00

booking: http://www.cltad.ac.uk

************************************************

Deterring and tackling plagiarism

Background

Plagiarism is growing problem in HE and worry about plagiarism is certainly

increasing. The good news is that many of the actions necessary to

do something about plagiarism are not complex. The bad news is that

plagiarism can only truly be addressed via a holistic approach that combines

many different actions. This workshop is designed to start you thinking

about how to deter plagiarism in ways that could even encourage student

learning.

Aims

To offer a mix of discussion, reviewing what the literature says and

practical advice for addressing plagiarism.

Outcomes

Following this workshop, you should be able to:

About the workshop leader

Jude Carroll is a staff developer at Oxford Brookes University, author

of A Handbook for Deterring Plagiarism in Higher Education (2002) and an

experienced workshop leader. She ha s offered workshops and conference

keynotes, both in the UK and internationally.

Bridget Murray, "Keeping plagiarism at bay in the Internet age." Monitor on Psychology 33:2 (February 2002).

Indiana University Writing Program, "Plagiarism: What It is and How to Recognize and Avoid It."

Ronald B. Standler, "Plagiarism in Colleges in USA." (2000)

Julie J. C. H. Ryan, "Student Plagiarism in an Online World." ASEE Prism Magazine (December 1998).

Studyguide.org: Research Paper Guide

e-skolar.com: Student Plagiarism