[as published in New Directions in Portfolio Assessment: Reflective Practice, Critical Theory, and Large-Scale Scoring, ed. Laurel Black, Donald A. Daiker, Jeffrey Summers, and Gail Stygall. 168-182. Portsmouth, New Hampshire: Boynton/Cook Heinemann, 1994.]We're going to tell three stories here. We'll begin with two that are fairly brief. The first is about a time we used something that could have been called portfolios to assess our students' performance in a writing program. The second tells how -- and a good deal more about why -- we stopped using them. We'll conclude with a third story in two voices that tells about practices that developed out of, and are built on, our experiences with portfolios, but that we think go beyond them to solve some of the problems we see with portfolios and with the kinds of scenes for writing that the portfolio method assumes and fosters.

St. Thomas University, where we teach, is a four-year liberal arts college with an enrollment of around fifteen-hundred full-time students. It is in the capital of New Brunswick, a small and not very prosperous Canadian province. Although St. Thomas' faculty comes from all over the world, our students are drawn overwhelmingly from within the province, and their backgrounds tend to be fairly provincial. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, St. Thomas offered its first-year students a many-sectioned, year-long, required writing course, which was taught by faculty volunteers drawn from departments across the disciplines. The key requirement for the faculty who taught the course was that they be active but not necessarily publishing writers, not that they know how to teach writing. From 1978 through 1985, a central feature of that program was that every student in every section wrote at least two (in some years, three) lengthy, research-based essays. The students chose their own subjects. Instruction focused on both process and outcome. The students did some preliminary research, wrote a proposal, and then took their essays through several drafts. As each student wrote and revised, the teacher of her section worked with her, one on one, in the role of coach. To a limited extent, her fellow students worked with her in workshops as collaborators.

These essays, in other words, were not simply written, commented on, and graded. (That, of course, was pretty much the default model of writing instruction at about that time.) Instead, in the context of ongoing feedback from teacher and fellow students, the student wrote, rewrote, and revised until she, her teacher, and her fellow students had negotiated some kind of stopping point: everyone was satisfied that the essay was finished, or the author decided she had done all she could at the time and would come back to finish it off later on.

Furthermore, none of these essays was graded by the student's own teacher. Instead, at the end of the year-long course, each student's essays were assigned ID numbers that hid the author's identity, gathered into a folder, and distributed to the writing program faculty for assessment and grading.

Before the folders were distributed for assessment; the writing faculty participated in training sessions where they learned to assess, rank, and grade anonymous essays holistically. When the folders were distributed, they were shuffled so that faculty received folders from several -- perhaps all -- of the sections of the course except their own. Each teacher then read and graded each essay. That done, the folders were collected and redistributed, so that every essay in every folder was read and graded by at least two members of the writing program faculty. Essays whose two marks varied by more than a full grade were then read by at least one other faculty member to see if a closer match could be achieved. The grades on the papers in a portfolio were then averaged and the resulting portfolio grade became the student's course grade.

One of our aims in this system of blind, holistic portfolio assessment was, of course, to achieve "reliable" evaluation and consistent grades. In many ways, this was the public rationale for instituting and maintaining this complex process. But what was more important to those of us concerned with the design of the program was that we wanted to change the relationship between writer and reader and writer and teacher. We were trying to structure a writing situation embodying motives for writing that would be different from those in the traditional composition course. Although the students were still writing at a teacher's bidding, their teacher was no longer also their evaluator; they were writing with that teacher's help, but that teacher was not their audience. That audience included not only fellow student-workshoppers, whose expectations they might expect to know; it also included those other teachers-evaluators, whose expectations would be more difficult for them to know. Because we wanted to diminish the value of the strategy of figuring out "what the teacher wants," we were trying to introduce greater distance between writer and assessor. Our thinking was that, if the students were not able to focus their attention on an individual teacher's particular standards and expectations, they would likely shift their focus to the task of writing for a more general audience the most informative and persuasive paper they could write.

We had begun to be painfully aware, moreover, that there were profound differences between the sort of writing activity that seemed to go on when writers were writing "for" someone -- especially when that someone was an evaluator of the writing -- and the kind that appeared to be happening when the writer was writing "to" someone to explain, inform, move, or persuade. We were beginning to see that when the audience for a text was the teacher, and when the teacher was not only coach and editor but also evaluator and audience, the situation became very peculiar indeed, and so did the pressures on the writer. We wanted to make writing more "real-world" for our students -- more like the writing Lee Odell and Dixie Goswami and others were beginning to show us that writers (as opposed to students) do.

Those faculty who finally received the portfolio essays, we naively thought, could act more like real readers than the teacher in the one-on-one, coach-advisor relation to the student. Equally important, we thought that introducing these "real readers" into the situation would help the teacher-coach and student collaborate in figuring out what an audience was likely to know and believe. In this situation, we hoped, the teacher could help the writer learn to use the pressure of audience as a tool for shaping her language "at the point of utterance" (Britton). This pressure would help the writer decide what to foreground and what to background, what to assume and what to state, what to argue for and what to assume as common ground, what to say now and what to put off until later. We thought we could create, that is, the sort of authentic situation Hunt claims supports language-learning ("A Horse Named Hans").

Like many stories of exploration in the teaching of writing, this one sounds as though it has a happy ending, but it turns out that things aren't quite that simple. There's often a second story that has already begun as the cowboys mosey off into the sunset.

During 1985-86, the last year of the writing program, we dropped the whole complex structure of portfolio evaluation, and we reorganized. The faculty teaching. the course each chose a subject or theme that the students would study and write about over the year. One instructor, an anthropologist, chose "writing"; another, from the English Department, chose "literacy"; and another, also from English, had his students undertake "an ethnographic study of the rhetoric of teaching." Here the aim of each section was that the students would produce a great deal of writing, most of it in the form of brief reports of research findings, but some of it in the forms of research proposals and feasibility studies. The ultimate aim was for each student to write a single scholarly article that would be "published" in a book of such articles written by the students in the course. Along the way, all of their writing was to be "public" -- that is, photocopied, read, and commented on, in workshop, by what Ken Bruffee had called the students' "knowledgeable peers" in the course. None of this writing was to be graded, however. Its function was not to provide material for assessment, but to take the students through (and thus educate them about) a collaborative scholarly process in which writing informed, persuaded, and was used by others in their own writing. As it turned out, instead of each student producing a portfolio of her writings, each course produced a portfolio of its students' writing. As Reither pointed out a few years later, we were putting students into a situation parallel to that of any scholar (cf. ''The Writing Student as Researcher") .

There were a number of reasons for reorganizing in this way. One was .that we had become deeply frustrated with the workshopping part of the course. Although we believed in its potential value and wanted to retain the feature in a revision of the course, workshopping -- as we had implemented it, at any rate -- had not worked for the students or for us. Because the students chose their own subjects, and all wrote on different things, they never became sufficiently engaged in the subjects others were writing about to offer suggestions on anything other than mechanics, syntax, and, occasionally, lines of argument. When it came to the more important question of whether or not the piece would inform or persuade, the students were stymied -- everything sounded good to them. And, truth to tell, the faculty were as limited as the students in this respect. Further, the tendency born of this limitation -- for the students to see themselves as apprentice English teachers rather than as real audiences -- pushed them into a mode of response that often tended to be (at best) condescendingly helpful and (at worst) censorious in the ways described a couple of years earlier by Nancy Sommers in her now-classic article on responding to student writing.

We had other, more theoretical reasons for the specific decision to abandon individual student portfolios. One was that they had failed to solve one of the most important problems we faced -- that our writing instruction, like most, created a situation in which the stand-alone written product became the center of everyone's concern. Although the teachers in this writing program had done everything they could to focus the students' attention on the process, in the end what mattered to both students and teachers were the products. Since those products were not, after all, especially interesting to anyone, what really mattered was the grade the products in the portfolio received. Here is one stomach-knotting indication that what really mattered was the grade: all

who taught the course over the years accumulated huge stacks of students' writing folders. Their authors rarely bothered to collect what they had worked so hard to write. They had their grades, and that, apparently, was what mattered. We now see, with the usual clarity of hindsight, that the problem was that the language in these portfolios had no intrinsic or authentic social function.

A second reason we discontinued using portfolios was that we came to believe that the portfolios only narrowly and peripherally served the students' short- and long-term needs. That is, while they may have served the students' needs to "do well" in their writing so that they could "get a good grade" in the course, in our experience they did not serve the students' rhetorical needs; they did not serve the human need to engage in discourse that is taken seriously by others for what it says and does in communicative, dialogic contexts. In the end, the primary -- indeed, all too often, the only and real -- function of the students' portfolios was to provide teachers with materials for assessing mastery of content, genre, and "writing abilities." Though portfolios gave teachers more, and more useful, data for assessment, they did not give students opportunities to effect change through writing. For most of the writers and most of the readers, that is, the language in the texts remained object, not gesture; artifact, not utterance; monologue, not dialogue.

A third reason we stopped using portfolios was that the need to assess and grade the products put the assessors in an untenable rhetorical position. In practice, our task was to rank, evaluate, and grade the portfolios. That assignment made it extremely difficult, if not impossible, to give those texts the sort of authentic assessment routinely given to texts encountered in out-of-school situations. The need to arrive at a grade abetted premature .closure , limited tolerance for (possibly deliberate) irrelevance, lowered confidence in the voice of the writer, promoted short-term processing, and in general rendered sympathetic, engaged reading -- if it could be achieved at all -- a matter of continual conscious effort. From a reader's point of view, the language of these essays could not in that situation attain the status of gesture or utterance or dialogue. We took small comfort in realizing that such is the position of all writing teachers engaged in formal assessment and grading, since that was precisely the situation we had been attempting to change.

The upshot is that, while we would not claim that the portfolio-assessment system we used in those years was anything but primitive -- even crude -- by today's standards, we would nevertheless suggest that, like all approaches that focus squarely on writing qua writing, assessment-by-portfolios still assumes a view of language and writing that is necessarily incomplete and inaccurate. The approach extracts writing from communicative, dialogic situations as if all that's involved in writing were the ability to turn out well-organized, clear, and coherent sentences, paragraphs, and essays -- and as if qualities like organization, clarity, and coherence were not functions of social situations. The social motives for and functions of writing get lost from view, not only for faculty charged with determining ranks and grades, but also for students charged with completing assignments to fill a portfolio with writing.

It was at about this point in the story that the gods descended in a machine and the writing program ceased to exist as a formal entity, leaving some of the teachers who had been involved to continue exploring these issues in a less formal way. By this time, none of us regretted that we could no longer marshal the forces necessary to conduct even an informal portfolio evaluation structure. We had learned that someone else reading a portfolio wasn't all that different from ourselves reading a term paper: the problem of the role of formal evaluation in the process hadn't been solved, or even much changed, by moving to portfolios and externalizing the evaluation. Thus, it does not really surprise us to read the conclusion of a recent press release on the electronic "Education Research List" announcing a new "pilot study that examines the viability of using writing portfolios as part of a large scale National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) assessment." The conclusion? The U.S. Department of Education says that "even when students were allowed to polish their writing, the pieces were generally not well-developed and did not communicate effectively. The students, for the most part, did not plan, think about, or revise their writing even when they had the opportunity."

Having said all this, however, we would like to make clear that nothing we have said denies the very real opportunities for teaching that can occur in portfolio-driven writing scenes. What we mean to suggest is that, for portfolios to work, everything depends upon having students who ardently and authentically wish to engage with the world through their writing, and who are already capable of effecting improvements through "dummy runs" in which communicative, dialogic reality is set aside, bracketed. For those many students who are not driven by such intentions and motives, there is little that portfolio methodology can do to transform the admonition to be better writers into an effective motive. It cannot help them shape their language at the point of utterance and create the imagined readers they need.

Our third story describes some consequences of our attempt to construct new practices, which build on our experiences and help us move toward situations which better support learning to use writing to get things done. Before we proceed to that story, however, it is appropriate to outline some of the theoretical framework that has come to inform our position. This frame work relies heavily on ideas drawn from Kenneth Burke and Mikhail Bakhtin.

In outlining this theory, we do not mean to suggest that there is a one-directional relationship between it and our practice. The theoretical framework is part of the story we're telling: it was in large measure our evolving practice that prepared us to see in these writers (and others) the kinds of ideas that had the power to inform and alter our practice. This dialectical relationship between what we do and what we perceive and believe is itself an important reason for our having adopted the practices we currently employ. If it works for us, the teachers, we suspect it might work for them, the students.

Kenneth Burke tells us in The Philosophy of Literary Form that "critical and imaginative works are answers to questions posed by the situations in which they arose. They are not merely answers, they are strategic answers, stylized answers" (1). For him, "every document bequeathed us by history must be treated as a strategy for encompassing a situation . . . as the answer or rejoinder to assertions current in the situation in which it arose" (109). These claims arise out of his notion of the "scene-act ratio," as outlined in the opening pages of his A Grammar of Motives. Burke's notion of the scene-act ratio has given us an important source of explanatory power, helping us understand what we were doing, what we thought we ought to be doing, and how we might go about doing it. In simple terms, Burke's scene-act ratio posits simply that a given scene ("setting," "background," "terrain," "situation") calls for, affords, and enables certain kinds of symbolic acts, and discourages, blocks, and prevents others. The scene, he says, "is a fit 'container' for the act" (3). It does not, of course, alone determine the symbolic acts that can or will occur in it, because agents, agencies, and purposes (the other terms in Burke's Pentad) are also determinants. However, "from the motivational point of view, there is implicit in the quality of a scene the quality of the action that is to take place within it. This would be another way of saying that the act will be consistent with the scene" (6-7). The scene thus "contains" a likelihood, a potential that certain kinds of symbolic acts will occur in it: certain symbolic acts are likely, appropriate, or proper, while other symbolic acts are unlikely, inappropriate, or even disallowed.

Burke's scene-act ratio helped us understand something about our own scenes for written acts. An academic journal, such as the Journal of Advanced Composition or Rhetoric Review, calls for, affords, and enables certain symbolic acts: statements of editorial policy, scholarly articles, publishers ' advertisements, notices of special issues, calls for submissions from other journals in the field, letters responding to articles in previous issues, notices of up coming meetings and conferences -- those sorts of things. Because academic journals provide scenes in which the members of a field of' practice carry on the academic enterprise, neither the Journal of Advanced Composition nor Rhetoric Review is likely to include in its pages advice to the lovelorn, barbecue recipes, romantic fiction, furniture or automobile advertisements, how-to electronics articles. (One of our favorite journals, PRE/TEXT, might, but not the Journal of Advanced Composition or Rhetoric Review.) The scene which is an academic journal in the field of composition studies is a "fit 'container' " for academic, scholarly symbolic acts. It is not "fit" for a wide range of other kinds of symbolic acts.

Not at all incidentally, this understanding offered us the materials for a critique of what we were doing and of portfolio assessment more generally. It would run something like this: a central problem with portfolios is that, because they occur in and help create scenes that focus students' attention upon the production of stand-alone written texts for assessment and evaluation, they work against students learning more than superficial lessons about writing for other purposes. Portfolios constitute scenes that do not obviously "contain" the ways in which a text's meanings evolve out of relationships with other texts. Portfolio-driven scenes thus deflect students' attention from such fundamental issues as a writer's motives for writing, where texts come from, who writes them, who reads them, and why. In sum, portfolio-driven scenes obviate serious examination of what it means to be a writer or a reader; they render invisible (if they do not actually eliminate) the communal and consensual interaction among writer, world, text, and reader that is involved in authorship.

Our reading of Burke in the context of our writing program's problems afforded a way to think about them that suggested that what we needed was a different scene in which writing could occur, one that would not only be different, but be seen to be different by the writers. Reading Bakhtin in that context gave us a way to think about how that scene might work.

The work of Bakhtin (or of the Bakhtin circle) in which we're interested is not that which deals mainly with theories of literature, with studies of the novel, and of Dostoevsky. The work we found particularly engaging concerns the ways in which language and languaging are social and is found in Marxism and the Philosophy of Language and (especially) in the essays collected in Speech Genres and Other Late Essays. This is where we found the claim that the utterance, not the phoneme, the word, the sentence or the text, should be taken as the basic unit of analysis for understanding language. It is work that made clear to us that no categorical differentiation between written and oral language needs to be made. Bakhtin begins with speech rather than writing, with parole rather than langue, with the contingent and context-bound rather than the clear and stable. He makes spoken, conversational language the norm in terms of which other kinds of language can be understood (it is almost as an aside, as though it were so obvious it hardly needed to be said, that he notes that "everything we have said here also pertains to written and read speech, with the appropriate adjustments and additions" [Speech Genres 69]).

This is where we hear that the utterance is invariably created, formed, and shaped as a response to a previous utterance or utterances, and that it is always created and formed and shaped in anticipation of a responding utterance. It is from this work that we learn that no piece of language is ever final, finished, polished and perfect; Bakhtin insists that all language is occasional, provisional, incomplete, open. Language, he tells us, is an unending dialogic web of cross-connected utterances and responses, each piece of writing or speaking' each utterance, depending on its occasion and context for its very existence, for its comprehensibility. The meaning of an utterance, he insists, is connected not to diction and syntax but to dialogue, occasion, intention or social relationships and processes. The same string of signifiers, he reminds us, can mean absolutely different things when uttered in different situations. Our speech, he is often quoted as saying, is filled to overflowing with the words of others -- and the phrases and sentences and discourses and texts of others, as well.

As we came to read him in the context of our evolving practice in classrooms, Bakhtin's view implied, for us at least, a dramatic change in the way we thought about the status of texts. In large part because of this reading, we take with increasing seriousness the idea that language is inherently dialogic and inextricable from its contexts of use; we have moved toward understanding it as what Bakhtin calls "continuing speech activity between real individuals who are in some continuing social relationship" (quoted in Bialostosky 220). As one of us has said elsewhere, it seems "more and more clear that talking about the properties of texts is like talking about the properties of reflections on water -- they clearly do have properties, but we are forced to be more and more circumspect about what we call properties and what we must acknowledge to be products of the viewer's angle of sight, the objects reflected, and the wind on the water" (Hunt, "Speech Genres").

Instances of language, then, cannot be understood in the abstract or out of their contexts of use. Even more important, Bakhtin's work implies that the sentence (or phrase, or word, or text) becomes, when moved from one context of use to another, a different utterance, and thus observations about it cannot be transferred back to the original context. We are never not engaged with an instance of language; we can never be only observers of it. Our readings of Burke and Bakhtin enabled us to understand that our goals as teachers ought to organize course and classroom scenes that would be "fit containers" for language that was truly communicative and dialogic -- scenes that abetted students in their efforts to understand the full dimensions and complexities of literate discourse.

A key tool in our kit-bag for setting such scenes is a written course

description we give our students at the beginning of each course we teach.

These course descriptions all have three main objectives: to provide an

overview that tells the students what they will be studying in the course;

to describe the method we call "collaborative investigation" by which the

students will undertake their study; and to describe our evaluative practices

-- what gets evaluated and how it is evaluated. All three objectives tie

in with this overall teaching objective: to provide a scene for dialogic

action by engaging all the students in the same project -- the same collaborative

scholarly investigation -- that calls upon them to learn by pooling information

and ideas. Here, in Russ Hunt's voice, is a brief narrative telling what

has happened during the first couple of weeks or so of this year's introductory

literature class.

|

To create in an introductory literature class a scene in which authentic dialogue is the central issue for everyone involved, each year I write a lengthy, thoughtful, and complicated course description, which attempts to make everything we're going to be doing as explicit as I can make it. During the first class session I introduce myself and explain that my intention is to make writing and reading do as much of the work of the course as I can, and that wherever possible I'll substitute them for oral language. I then hand each student a copy of the document and also another, one-page document titled "In Class Today," that simply asked the students to read the longer document carefully, mark confusing, interesting, questionable, or threatening passages, and then to take a sheet of paper and write for ten minutes, saying whatever seemed important to say about the course introduction. It also made clear to the students that what they wrote would be read by others in the class. When everyone had time to read the document and about ten minutes to write, I formed them into groups of five or so and asked them to read each others' work, reminding them that it's to be expected that most of what was written wouldn't be of great interest, and their aim should be to find what was and ignore the rest. Finally, after everyone had read each document, each group discussed them and decided on two or three marked passages that they thought needed to be brought to everyone's attention. A member of the group other than the author was designated to read the passage or summarize it. We went around the class from group to group and each raised a concern or an issue for discussion by the whole group and response by me or another class member. Among the issues marked by more than two readers this term were the following:

This year, the first assignment in that class (after everyone had a chance to make sure she understood the course and how it would work, and to switch to another section if that's what she wanted) was to go out and find a text that she recommended that everyone read. The student then wrote a recommendation of it for class reading and decision, and brought a copy of the text to class. (Again, the assignment was explained in writing.) During the next class session, I formed random groups and asked each group to give all its recommendations to another group, who read them and asked questions that they thought would help them make a choice of what to read. The questions were to be in writing, attached to the recommendations. The original recommenders then answered -- again in writing -- as many of the questions as they could in a few minutes, and gave the answers back to the questioners, who made their choice, obtained the original of the text from the owner and made arrangements to make copies and read it. Again, one of the central aims of this activity was to create a different scene for writing and reading, one in which the intentional substance of the text was the focus of attention, rather than its quality; where the text was used as the medium for dialogue rather than the object of study itself. If your recommendation was persuasive, its readers were persuaded; that was your evidence of its success. In one case, for example, Ulrike (all the names have been changed) recommended a story called "Chicken," which she described as dealing with "a stolen chicken brought home for food and feathers" which, after its head is cut off, "jumps up as if it still has a head and mind of its own." The group asked her why she decided to read it, and she conceded that "actually I was kind of appalled by the story. I felt that it could be a story that would raise quite a bit of discussion." The group ultimately decided to read the story because, as they said, "we are curious about what makes this short story different." In the event, after reading the story and writing individual responses that they shared in the next class, the group was deeply divided about the story. The division is reflected in their responses: Emily: "Reading about a chicken running about without its head was awful."The consensus document the group arrived at in turn reflected their division: As a group we had different opinions. In some ways we thought the short story was awful, but then again it has a lot of meaning. For instance, one thought it would bring the class to the true meaning of where our food comes from. Another person thought it was awful that an innocent bystander would have to read such a story. It was difficult to read a story about a chicken with its head cut off running around. We all hoped that the chicken would get away, and live forever, instead of ending up on our dinner tables.Ultimately, on reading the document, the class decided not to read "Chicken." But the fact that reading the document had actual consequences changed how it was written and read in ways that Burke and Bakhtin help us to understand. This is a scene that affords dialogue. The class would continue to use writing and reading -- the students', mine, that of professionals -- in ways similar to this throughout the rest of the course. |

But this narrative addresses only one of the issues lying behind the question of portfolio evaluation. It may deal with the problem implicit in a scene where portfolio-writing is a central purpose, but it does not address the more critical problem: what gets evaluated, if not product? And if language is agreed to be, as Bakhtin insisted it was, provisional, temporary, and incomplete -- incomprehensible out of its dialogic ecology -- how do we decide when to extract a core sample for evaluation, or when to take our photograph to freeze the process for analysis?

Burke tells us that for most of our students, especially the ones who need our help the most, evaluation creates a scene that makes evaluation itself the central purpose for the product in the first place. This means that we need another strategy altogether.

We think we have one. Although each of us manages the details of evaluation in ways that are slightly different in detail, we all follow a basic pattern that dispenses with lectures, teacher-guided discussions, textbook readings, assigned term papers, and exams. Although our students write in and for almost every class, this writing takes the forms of proposals, recommendations, progress reports, informal feasibility studies, reports of findings, inkshedding, and the like. Although the goal of writing a course book (our version of a kind of course portfolio) is always in mind, much -- perhaps most -- of this writing is meant to be used in the investigation and then set aside as the investigation goes on. Some of it will be revised and used in the course book, and much will be thrown away, but all of it -- even the course book -- is for the students' use; and the teacher, who often does not even see it, neither comments on it nor grades it.

In our courses, then, evaluation takes a radically different form than in the traditional university writing or "content" course. The following tells how evaluation was handled in one of Jim Reither's recent courses.

English 2-394, Selected Themes: Writing and Reading about

Literature, was a one-semester course offered primarily to second-and

third-year students. In the written description I gave my students at the

beginning of the course, I told them that

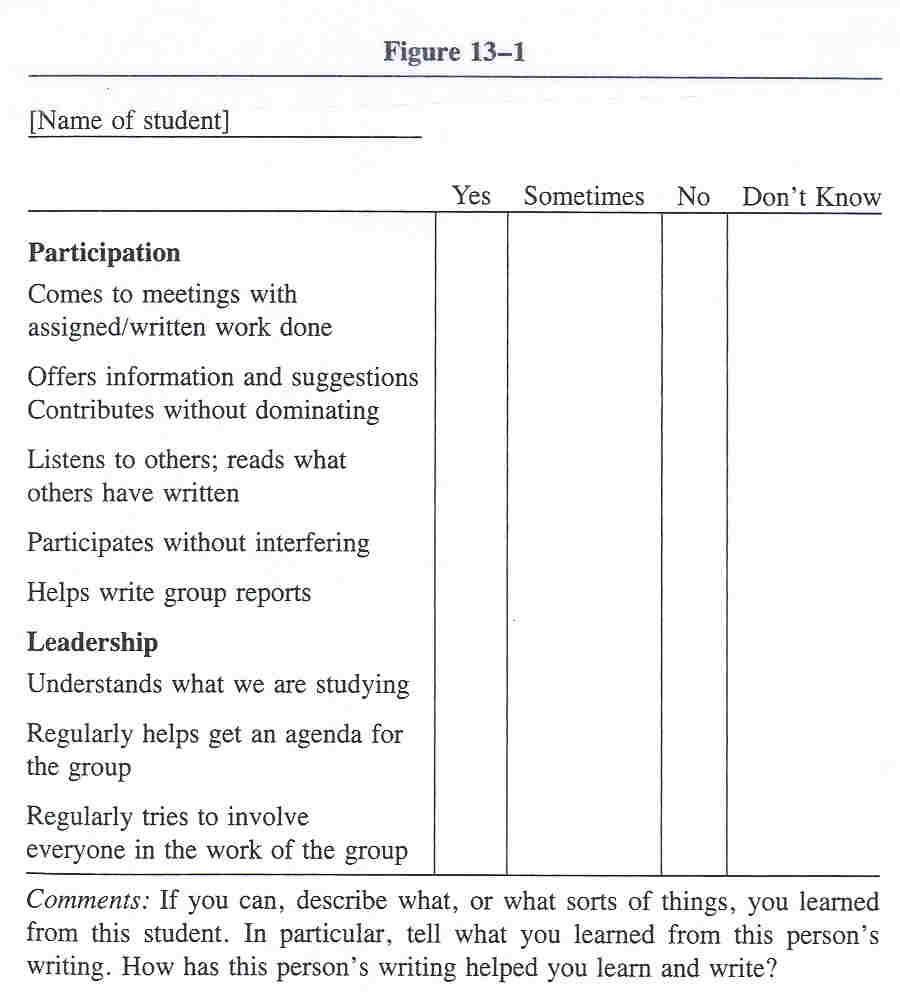

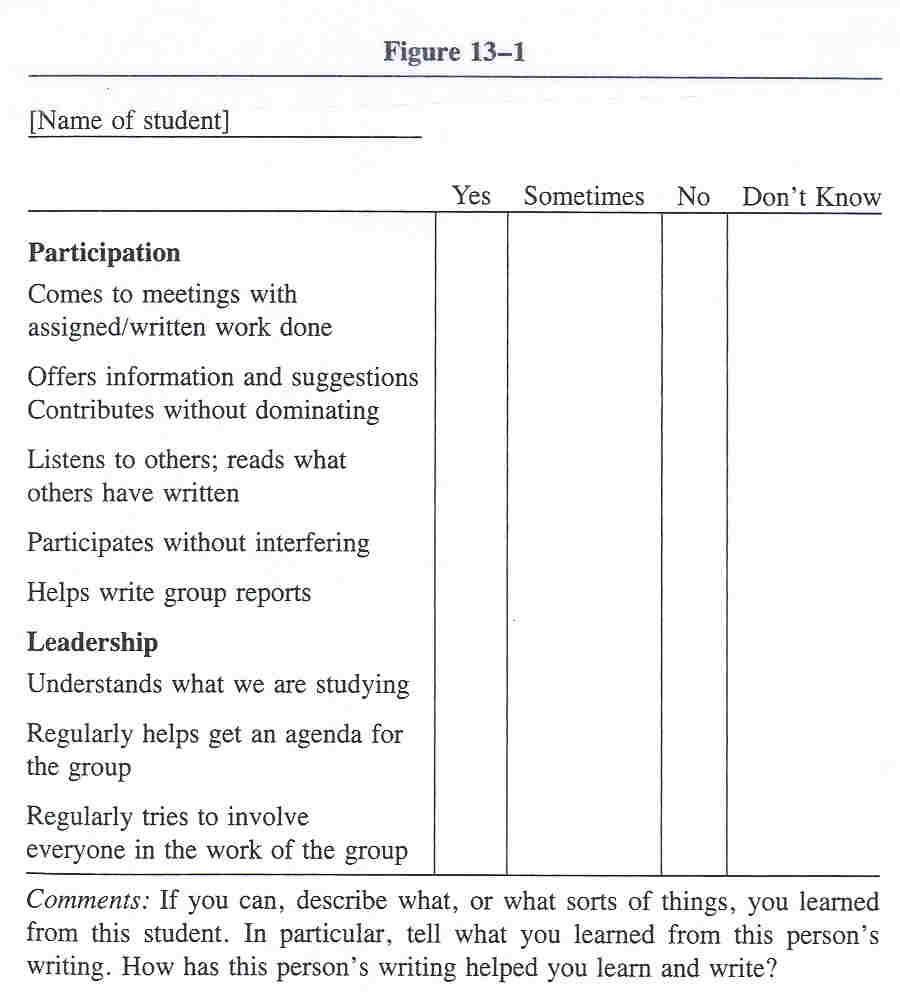

I hope it's obvious [from what's come earlier in the description] that this course will challenge students to develop and extend their abilities to communicate with others in persuasive ways, to listen to others and encourage them to speak and write, and to help others teach and learn -- in short, to cooperate and collaborate. The course will not put the usual premium on competition -- on "doing better" than or "beating" others. . . . Since there are no tests, exams, or term papers in the course, and you will often be working with others when I'm not present, we need alternative ways to evaluate student achievement. I will devise an evaluation form which asks questions about participation (e.g., whether or not a student shows up for meetings with assigned work done; takes part in the work of the group; listens to others; offers information and suggestions; . . . and about leadership (e.g., understands what we are studying; helps set an agenda for the group; . . ). This form will also ask about students' goals and their perceptions of one another (How do you want others to see you? How do you think others actually see you? How do you see others?)I went on to explain that full participation in the course -- coming to class, doing the assignments -- would guarantee a grade in the C range, but that a grade of B or A would require both full participation and clear evidence of leadership. Participation would be measured quantitatively: I would record attendance and give students credit for every activity or assignment they took part in. Leadership would be measured qualitatively, by the students, since only they could know what they have learned from one another. To get access to what they know about one another, twice in the course I asked students to fill out a version of the questionnaire mentioned above. This year, in an effort to tell my students very specifically what participation and leadership mean in my courses, I devised a questionnaire that began with self-evaluation by asking the students to tell how they hoped others would see them and how they think others might actually see them. The questionnaire then listed every student in the course and asked the student filling out the questionnaire to indicate how she saw those students, using a version of the form shown in Figure 13-1. |

What we are trying to do with questionnaires like this, of course, is re-define and reshape the way the students see themselves and learning. Other teachers who use this method use different questionnaires. But there is general agreement, among those of us concerned, that what we want is to use our methods of evaluation as part of an attempt to set new scenes for our students to write in, scenes that will redefine and reshape the way the students see themselves, their relationship to one another and the teacher, and the process of learning. What we seek is a method of evaluation that will not infect the scene for writing with secondary motives, but which will still allow us with some confidence to tell the rest of the university, and our society, that our students have achieved a certain level of competence. We are, that is, attempting to take audience into account in our evaluation procedures: we need to tell something to our students, to each other, to ourselves, and to the world outside (represented first by the registrar's office). This strategy, we believe, allows us to do this.

There, then, are our stories. Like all stories, what their points are and how they'll be understood and passed on is a function of the situation in which they're told, the tellers, and the audience: the scene. We hope that they open the doors to further dialogue.